The Brutal Reality of App Templates: A 3,500-Word Architectural Teardown

The Brutal Reality of App Templates: A 3,500-Word Architectural Teardown

As a senior architect, I've seen more codebases than I care to remember. I've been parachuted into failing projects, tasked with auditing multi-million dollar platforms, and asked to bless the technical direction of ambitious startups. More often than not, the journey begins with a simple, seductive idea: "Let's buy a template." The logic seems sound. Why reinvent the wheel when you can buy a pre-built car, give it a new paint job, and start selling tickets? This is the siren song of the app template marketplace, a world filled with promises of quick launches and passive income. Today, we're going to strap a portfolio of these templates to the operating table and perform a full architectural autopsy. We’ll dissect their code, question their design, and expose the often-painful gap between a functioning .apk and a viable, scalable business.

The allure is undeniable. Marketplaces are flooded with source codes for everything from hyper-casual games to complex social media clones. But beneath the polished screenshots and feature lists lies a complex reality of technical debt, architectural rigidity, and intense market saturation. The dream of a quick flip often devolves into a nightmare of refactoring, debugging undocumented code, and fighting for visibility in an impossibly crowded ecosystem. While you can certainly find a vast selection of Android game source codes, the quality and long-term viability vary dramatically. True success requires more than just a purchase; it demands a deep understanding of the underlying architecture and a strategic plan for differentiation. For developers seeking a reliable foundation, vetted platforms like the GPLPal for professional assets ecosystem offer a more curated starting point, but the fundamental principles of due diligence remain the same. Let's begin the teardown.

Bounce3D Jumping Ball Android

The journey starts with a quintessential example of the hyper-casual genre. Exploring the Get Android Game Bounce3D Jumping Ball template reveals a familiar one-tap gameplay loop designed for maximum ad revenue and minimal user commitment. The premise is simple: guide a bouncing ball down a helical tower, avoiding obstacles. Architecturally, this is the "hello world" of 3D game development. It's built to be reskinned, repackaged, and deployed at scale, flooding the app store with dozens of near-identical clones. The core systems are predictable: a physics-based controller for the ball, a procedural or pre-fabricated level generator for the tower segments, and a simple state machine to handle game start, play, and game-over conditions. The monetization hooks (AdMob, in this case) are deeply integrated, often triggering interstitial ads at every possible juncture—level completion, player death, even pausing the game. While this maximizes impressions, it creates an abrasive user experience that contributes to sky-high churn rates. The primary challenge here isn't technical; it's strategic. How do you make your version stand out when there are a thousand others with different color palettes but identical mechanics?

Under the Hood

-

Engine/Framework: Built on Android Studio, likely using a native Java/Kotlin stack with a lightweight 3D rendering library like OpenGL ES or a simple game engine wrapper.

-

Core Logic: The ball's movement is managed via a simple physics simulation, reacting to user input (a screen touch and drag to rotate the tower). The helix tower is almost certainly generated from a set of pre-designed prefabs (straight piece, gap piece, "death" piece) that are instantiated in a semi-randomized sequence.

-

State Management: A basic Singleton or static class probably manages the game state (e.g.,

GameState.PLAYING,GameState.GAMEOVER). This global state manager holds the score, level number, and other session-critical data. -

Monetization Layer: The AdMob SDK is likely initialized in the main Activity, with static helper methods called from various points in the code to show banner ads and trigger interstitial video ads. The integration is functional but often architecturally intrusive.

Simulated Benchmarks

On a mid-tier Android device (e.g., Samsung A-series, ~4GB RAM), the application maintains a fairly stable 50-60 FPS. The simplicity of the geometry and shaders keeps the GPU load minimal. However, performance dips can be observed during the aggressive loading and display of interstitial video ads, where the app can freeze for 500-800ms as the ad SDK takes over the main thread. Memory consumption is low, hovering around 120-180MB during active gameplay. The APK size is small, typically under 50MB, which is a key requirement for the hyper-casual market to facilitate quick, impulse downloads.

The Trade-off

You acquire a fully functional, market-ready game loop for a negligible upfront cost. The time-to-market is theoretically measured in hours, not months. The trade-off is that you inherit an architectural dead-end. The codebase is not designed for expansion. Adding new mechanics, a meta-game (like a currency system or skin unlocks), or a more sophisticated level generation algorithm would require a significant refactor, if not a complete rewrite. You are buying a disposable product, not a platform. The business model is predicated on volume and luck—launching dozens of reskins and hoping one catches the algorithm's favor for a week or two. It's a game of arbitrage, not a foundation for a brand.

Super Chat – Android Chatting App with Group Chats and Voice/Video Calls – Whatsapp Clone v3.6.1

Here we see a dramatic escalation in complexity and risk. It's one thing to clone a simple game; it's another entirely to clone WhatsApp. A quick Inspect Android App Super Chat shows a template that promises the holy grail: a feature-complete messaging application with one-to-one chat, group chat, and even voice/video calls. The feature list is impressive, but as an architect, it sets off every alarm bell in my head. Real-time communication at scale is one of the most difficult engineering challenges. It requires a robust, low-latency, and highly concurrent backend, sophisticated client-side state management, and an unwavering focus on security and privacy. This template likely provides a functional UI and a basic client-server architecture, but the devil is in the details. The backend is probably a standard LAMP/LEMP stack with WebSocket or long-polling for real-time updates, which will crumble under any significant user load. The voice/video call feature almost certainly relies on a third-party WebRTC service like Twilio or Agora, which introduces significant operational costs that the template's price tag conveniently ignores.

Under the Hood

-

Client Architecture: An Android Studio project, likely using a traditional MVC or MVP pattern. The UI is probably built with standard XML layouts and managed by Activities and Fragments. Data persistence for messages is handled by a local SQLite database, possibly via the Room Persistence Library.

-

Backend Communication: The critical component. It's likely using a REST API for authentication and profile management, and WebSockets (via a library like Socket.IO) for the real-time chat functionality. The backend itself is almost guaranteed to be a monolithic PHP or Node.js application.

-

Real-time Media: Voice and video calls are not peer-to-peer in any scalable model. The template will integrate a third-party SDK that handles the complex signaling (via STUN/TURN servers) and media relay required for WebRTC to function reliably across different network conditions.

-

Security: This is the biggest concern. End-to-end encryption is a non-trivial feature. This template likely offers transport-layer security (HTTPS/WSS) at best. True E2EE, like the Signal Protocol used by WhatsApp, is a complex cryptographic implementation that you will not find in an off-the-shelf product like this.

Simulated Benchmarks

On the client-side, the app's performance will be acceptable for a few dozen contacts and active chats. However, as the local SQLite database grows with thousands of messages and media files, UI performance, especially on launch, will degrade significantly without proper indexing and data pagination. The backend is the real bottleneck. A typical cheap VPS running the provided PHP backend might handle 50-100 concurrent WebSocket connections before CPU and I/O limits are reached, leading to message delays and connection drops. A properly scaled chat backend requires a distributed architecture, message queues, and load balancers—an infrastructure costing thousands per month, not the $10/month server the template developer might suggest.

The Trade-off

You get a visually convincing prototype that can impress non-technical stakeholders. It provides a massive head-start on the UI/UX for a messaging app. The trade-off is that you are buying a technically insolvent platform. The architecture is fundamentally unscalable and likely insecure. To turn this into a real product capable of supporting even a few thousand active users, you would need to throw away the entire backend and rewrite it from scratch using appropriate technologies (e.g., Erlang/Elixir, Go, or a managed service like Firebase). You are not buying a WhatsApp clone; you are buying a UI theme and a set of architectural problems to solve.

Street View With GPS Map with AdMob Ads Android

This template falls into the "utility" category, a popular niche for template-based apps that aim to provide a simple service monetized through ads. To Analyze Android App Street View With GPS Map is to see an app that is essentially a wrapper around a public API—in this case, the Google Maps and Street View APIs. The value proposition is convenience: it packages a specific, sought-after feature into a standalone, easily discoverable app. Architecturally, these apps are trivial. They consist of a few screens: a main screen with a map view, a search bar, and perhaps some UI elements to configure map settings. The core logic involves making API calls to the Google Maps Platform, parsing the results, and displaying them within the app's UI components (a MapView and a StreetViewPanoramaView). The entire application is a thin client that depends entirely on a third-party service. The monetization model is straightforward AdMob integration, placing banner ads on the screen and potentially interstitial ads between actions.

Under the Hood

-

Core Technology: This is an Android Studio project built around the Google Maps Platform SDK for Android. The majority of the code is dedicated to initializing the map, handling user permissions for location access (ACCESS_FINE_LOCATION), and configuring API requests.

-

API Integration: The app's functionality is directly tied to the developer's Google Cloud Platform project and their API key. All map tiles, location data, and Street View imagery are fetched directly from Google's servers.

-

UI/UX: The user interface is typically built with standard Android components. A

MapViewfragment displays the map, and anEditTexthandles search queries. The logic to translate a search query into coordinates (geocoding) and then request a Street View panorama is the main piece of custom code. -

Business Logic: There is almost no business logic. The app is a stateless frontend for Google's services. The only "logic" might be saving recent searches to

SharedPreferencesor a simple local database.

Simulated Benchmarks

Performance is almost entirely dependent on the performance of the Google Maps SDK and the user's network connection. The app itself has a very small computational footprint. On a modern device, interaction is smooth. The key performance metric to watch is not FPS, but API usage. The Google Maps Platform has a generous free tier, but it is not unlimited. A successful app with tens of thousands of users could quickly generate thousands of map loads and Street View requests per day, potentially incurring significant API costs. A developer who launches this app without carefully monitoring their GCP billing dashboard is in for a nasty surprise. The AdMob integration can cause minor UI stutters, as is typical.

The Trade-off

The development effort is near-zero. You are essentially buying a pre-configured shell for a public API. The trade-off is that you have no moat, no unique value proposition, and your entire business is at the mercy of Google's API terms of service and pricing. Google could change its API pricing, deprecate an endpoint, or even decide your app violates their ToS, and your business would cease to exist overnight. Furthermore, the Play Store is littered with thousands of identical "GPS Map" and "Street View" wrapper apps, making discoverability a monumental challenge. You are competing in a market where the only differentiator is the app icon.

Bundle 15 Games (Admob + GDPR + Android Studio)

This product represents the "shotgun" approach to the app template business. Instead of one polished template, you get fifteen hyper-casual game source codes in a single package. This is the epitome of quantity over quality. Each of the 15 games will be a variation on a well-worn theme: endless runners, tap-to-jump games, simple physics puzzles, and so on. They are all designed in Android Studio, share a similar simplistic architecture, and are pre-configured with AdMob and a basic GDPR consent screen. From an architectural perspective, this bundle is a collection of liabilities. You are not acquiring a versatile framework; you are acquiring 15 distinct, rigid, and likely poorly-documented codebases. The effort to simply open, understand, reskin, and repackage all 15 of these apps is significant. Each one requires a unique package name, new graphics, a new Play Store listing, and its own AdMob ad unit IDs. The promise of "15 games" quickly translates into 15 separate, tedious deployment pipelines.

Under the Hood

-

Architecture Pattern (or lack thereof): Expect 15 separate Android Studio projects. There will be no shared code, no common library, and no consistency in coding style or architecture. Some might use a basic MVC, others might be a single monolithic Activity. Code quality will be highly variable.

-

Common Elements: The only truly common elements are the integrations. Each project will have the AdMob SDK dependency in its

build.gradlefile and will likely use Google's User Messaging Platform (UMP) SDK to display a GDPR consent dialog on the first launch for European users. -

Code Reusability: Zero. The code for "Game A" is completely isolated from "Game B". The value is not in the code itself, but in the sheer number of ready-to-compile game loops you receive.

-

Asset Structure: Each project will have its own

res/drawableandres/rawfolders for images and sounds. The primary "work" involved in using this bundle is to systematically replace all of these assets across all 15 projects.

Simulated Benchmarks

Each individual game will have performance characteristics similar to the Bounce3D example: low resource usage, generally high FPS on mid-range devices, and potential stutters from ad loading. The real "performance" metric here is developer time. Let's estimate: 30 minutes to understand the asset structure of one game, 2 hours to create and export a new set of graphics, 30 minutes to replace assets and package names, and 1 hour for testing and creating a Play Store listing. That's 4 hours per game, multiplied by 15, equals 60 hours of repetitive, low-skill work just to get the "reskinned" versions out the door. This assumes no bugs or issues with the original source code, which is a generous assumption.

The Trade-off

You are buying lottery tickets, in bulk. The strategy is to overwhelm the market, hoping that one of the 15 reskinned apps gets a brief, profitable moment in the spotlight. You are trading a small amount of money for a massive amount of your own time. The architectural trade-off is absolute: you sacrifice any notion of quality, maintainability, or extensibility for sheer volume. This is the digital equivalent of a factory churning out disposable trinkets. There is no brand to be built, no community to be fostered, and no technical asset of any lasting value being created. It's a pure arbitrage play on developer time versus potential ad revenue.

Ball Catcher – Android Game Unity

Here we shift from native Android Studio projects to the Unity engine, a dominant force in mobile gaming. Ball Catcher is another hyper-casual concept: objects fall from the top of the screen, and the player controls a container at the bottom to catch them. This template demonstrates the power and pitfalls of using a sophisticated game engine for a simple task. The Unity editor provides a powerful visual workflow, making it incredibly easy to create prefabs for the falling objects and the catcher, define their physics properties using Rigidbodies and Colliders, and script the basic game logic in C#. The architecture is component-based, following Unity's standard design patterns. A GameManager script, often implemented as a singleton, will control the game state, score, and spawning logic. The falling objects will be instantiated from prefabs, and the catcher's movement will be tied to user input via the Input class.

Under the Hood

-

Engine: Unity 3D, which means the project is cross-platform by nature (though this template is sold for Android). The language is C#.

-

Core Architecture: An Entity-Component-System (ECS)-like model, which is Unity's standard. Game objects (the catcher, the falling balls) are containers for components (like

Transform,Rigidbody2D,SpriteRenderer,Collider2D). -

Spawning Logic: The

GameManageror a dedicatedSpawnerscript will use a coroutine (IEnumerator) with ayield return new WaitForSeconds()loop to periodically instantiate ball prefabs at random positions at the top of the screen. -

Performance Optimization: A key consideration in a game like this is object pooling. Constantly instantiating and destroying game objects can lead to garbage collection spikes and performance stutters. A well-designed template will use an object pool to recycle the falling balls instead of destroying them, significantly improving performance. A poorly-designed one will not, and this is a major red flag for the code quality.

Simulated Benchmarks

A simple 2D Unity game like this has a very low performance overhead. On any modern smartphone, it should run at a locked 60 FPS without issue. The main performance variable is the implementation of the spawning system. Without object pooling, running the game for several minutes with a high spawn rate could lead to memory fragmentation and noticeable hitches as the garbage collector runs. With object pooling, performance remains perfectly smooth indefinitely. The APK size for a simple Unity game is typically larger than a native Android one, often starting in the 40-60MB range due to the inclusion of the engine runtime.

The Trade-off

You get a project built in a powerful, industry-standard engine. This makes it far more extensible than a native Android Studio game template. Adding new features, visual effects, or more complex mechanics is significantly easier within the Unity ecosystem. The trade-off is a higher barrier to entry if you are not already familiar with Unity and C#. You are also locked into the Unity ecosystem, with its own licensing and service terms. Furthermore, the core problem of the hyper-casual market remains: the gameplay itself is generic. While you have a better architectural foundation to build upon, you still need a compelling creative vision to differentiate your product from the sea of other "catcher" games.

Throw Color

Throw Color is another entry in the hyper-casual genre, likely built in Unity or a similar cross-platform engine. The gameplay probably involves tapping to "throw" a colored ball or projectile at a rotating target, matching the color of the projectile to the segment of the target it hits. This is a classic timing and reflex mechanic, seen in countless popular mobile games. Architecturally, it's a step up in complexity from a simple "catcher" game. The core system involves a rotating object (the target wheel) and projectile physics. The rotation can be handled by animating the Transform.rotation property in an Update loop. The projectile logic involves instantiating a ball and applying a force to it using Unity's physics engine. The most critical piece of logic is the collision detection and color-matching check. This is typically done in the OnCollisionEnter or OnTriggerEnter methods, where the script checks the tags or a component's property on both the projectile and the target segment to see if they match.

Under the Hood

-

Target Logic: The rotating wheel is likely an empty GameObject with several child objects representing the colored segments. Each segment has its own

Colliderand a script or property defining its color. -

Rotation Mechanics: The wheel's rotation speed could be constant, or it could increase over time to ramp up the difficulty. This is controlled by a simple variable in the

Updatemethod of aRotatorscript. -

Projectile System: A

PlayerControllerorShooterscript listens for user input (e.g.,Input.GetMouseButtonDown(0)). On input, it instantiates a projectile prefab from an object pool and usesRigidbody.AddForce()to launch it towards the target. -

Scoring and State: A central

GameManagersingleton tracks the score, the current level, and the game state. It receives events or direct calls from the collision logic to update the score when a correct hit is made and to trigger a game-over sequence on a miss.

Simulated Benchmarks

Performance should be excellent. This type of game involves a small, fixed number of objects on screen at any one time. The physics calculations are simple, and the rendering load is minimal. The game should maintain a solid 60 FPS even on low-end devices. Memory usage will be low, likely under 200MB. The key area for potential optimization is in the visual effects. If the game uses complex particle systems for hits and misses, these could cause "overdraw" on mobile GPUs, leading to frame drops. A well-optimized template will use simple, lightweight particle effects or sprite-based animations.

The Trade-off

You're buying a proven, addictive game mechanic. The core loop is solid and known to retain users (at least in the short term). The Unity project structure gives you a good foundation for visual customization and level design. The trade-off, once again, is extreme market saturation. "Color wheel" and "knife throwing" style games are a dime a dozen. Your ability to succeed will depend almost entirely on the quality of your "juice"—the visual and audio feedback that makes the game feel satisfying to play. This is an art, not a science, and it's not something a template can provide. You also inherit the design decisions of the original developer, which might include a poorly structured level system or hard-coded difficulty curves that are difficult to change.

Background remover

Returning to utility apps, we find the "Background remover." This is a highly appealing category for users, but technically, it's one of the most challenging to implement well. High-quality, AI-powered background removal is computationally expensive and requires sophisticated machine learning models. A template promising this feature is almost certainly doing one of two things: either it's using a very basic, non-AI algorithm (like a "magic wand" tool based on color similarity, which produces poor results), or it's acting as a frontend for a third-party cloud-based API (like remove.bg). Given the context of app templates, the latter is far more likely. The app's architecture would be simple: an Activity to let the user select an image from their gallery, an asynchronous task (using AsyncTask, Coroutines, or RxJava) to upload the image to the API endpoint, and a view to display the returned image with a transparent background. The "AI" isn't in the app; it's in a remote server farm.

Under the Hood

-

Core Structure: A simple, multi-activity Android application.

MainActivityhandles image selection via anIntent. AResultActivitydisplays the final image. -

API Client: The heart of the app is an HTTP client (like OkHttp or Retrofit) configured to communicate with the background removal service's API. The request will be a multipart form-data upload containing the user's image and an API key.

-

Image Handling: The app uses Android's

Bitmapclass to load and handle images. Care must be taken to handle large images correctly to avoidOutOfMemoryErrorexceptions, which is a common pitfall in poorly written image-processing apps. This involves down-sampling the image before uploading if it's too large. -

Monetization & Costs: The business model is tricky. The app is likely monetized with AdMob ads. However, the third-party API it relies on is not free. Each API call costs money. The developer is betting that the ad revenue generated per user will be greater than the API costs they incur. This is a precarious financial balancing act.

Simulated Benchmarks

The app's client-side performance is secondary to the network performance and the API's processing time. The user experience is defined by the "time-to-result." This includes the time to upload the image (dependent on the user's connection speed and image size) and the time for the server to process it. For a 2MB photo on a decent 4G connection, this entire process could take anywhere from 5 to 15 seconds. The app itself will consume a moderate amount of memory while the Bitmap is loaded, potentially 100-300MB depending on the image resolution. A crash (OutOfMemoryError) is a high risk if the template doesn't handle image scaling properly.

The Trade-off

You acquire an app with a very powerful and desirable core feature without having to develop any of the complex AI technology yourself. The user-facing product can look very impressive. The trade-off is that you are building a business on top of another business. Your profit margin is the razor-thin slice between your ad revenue and your API costs. You are also completely dependent on the third-party service for uptime, quality, and pricing. If they raise their prices, your business model could become unprofitable overnight. If their service goes down, your app is completely non-functional. You own the customer relationship, but you don't own the core technology.

Ball Jump – Unity Game

Ball Jump is another variation on the hyper-casual theme, likely a 2D or 2.5D "endless climber" or "jumper" game. The player taps the screen to make a ball jump from one platform to another, trying to get as high as possible. Like Ball Catcher, this is a prime candidate for a Unity-based template. The architecture will be component-driven and centered around a few key scripts. A PlayerController script will handle the jumping mechanic. This is usually implemented by applying an upward force to the ball's Rigidbody2D component when the screen is tapped. The platforms themselves will be prefabs, instantiated by a LevelGenerator or PlatformSpawner script. A critical architectural decision is how the world moves. Either the platforms are spawned and move down the screen towards the player, or the camera follows the player as they move up through a static or procedurally generated world. The latter approach is more common and feels more natural to the player.

Under the Hood

-

Player Physics: The core of the game is the

Rigidbody2Don the player object. The jump force, gravity scale, and physics materials (for bounciness) are all tweaked to get the right "game feel." APlayerController.csscript will contain theif (Input.GetMouseButtonDown(0))check and therb.AddForce(Vector2.up jumpForce)call. -

Level Generation: A spawner script tracks the position of the highest platform. As the player moves up, the script procedurally instantiates new platform prefabs above the camera's view and destroys old platforms that are far below, keeping the scene optimized.

-

Camera Control: A simple

CameraFollow.csscript will be attached to the main camera. In itsLateUpdate()method (to ensure the player has moved first), it will smoothly update its own position to match the player's Y position, but not its X position, creating the classic vertical scrolling effect. -

Game State: A

GameManagersingleton detects when the player has fallen off the bottom of the screen (e.g., by checking if `player.transform.position.y

Simulated Benchmarks

This is a computationally trivial game. The physics calculations for a single jumping ball are minimal. The number of objects on screen is kept low by the procedural destruction of old platforms. The game should maintain a flawless 60 FPS on virtually any device made in the last 5-7 years. Memory usage will be stable and low, typically under 150MB. The only potential performance issue could arise from a poorly implemented level generator that fails to destroy off-screen platforms, leading to a gradual increase in object count and an eventual slowdown over a very long play session.

The Trade-off

You're buying a clean, simple, and proven game loop built on a solid engine (Unity). The code is likely to be straightforward and relatively easy to modify for someone with basic C# skills. The trade-off is the sheer, overwhelming saturation of this specific game mechanic on the app stores. Games like Doodle Jump perfected this genre over a decade ago. To find success, you need a truly unique artistic style, an innovative new twist on the mechanic, or a powerful marketing strategy. The template gives you the "what" (a jumping ball game), but provides zero help with the "why" (why anyone should play your version over the thousands of others).

Traver – Advance City & Travel

This template, Traver, shifts us back to the utility app space, targeting the lucrative travel niche. It promises to be an "Advance City & Travel" guide. Architecturally, this type of app is a content-delivery platform. It's designed to display curated information—points of interest, restaurants, hotels, city guides—in an organized and visually appealing way. The core of such a template is not in its real-time functionality but in its content management. The data (listings, descriptions, images, coordinates) is either hard-coded into the app (a terrible, inflexible approach) or, more likely, fetched from a remote backend via a REST API. This means that purchasing the app template is only half the battle; you also need to set up, host, and populate the backend server with content. The backend is often a simple CMS, like a WordPress site with custom post types or a dedicated admin panel built with a PHP framework.

Under the Hood

-

Client Architecture: A standard native Android app with multiple Activities/Fragments for different content types (e.g.,

CategoriesActivity,ListingDetailActivity,MapActivity). It will likely useRecyclerViewextensively to display lists of places. -

Data Layer: The client app will have a data layer responsible for fetching content from the backend. This would use a library like Retrofit to define the API endpoints and GSON/Moshi to parse the JSON responses into local data objects (POJOs/data classes).

-

Backend/CMS: The unseen but essential component. The template will come with a separate package containing the PHP/MySQL backend. This will include an admin panel where the app owner can log in to add, edit, and delete cities, places of interest, and other content.

-

Offline Support: A more sophisticated version of this template might include a basic offline mode. When the app fetches data, it would cache it in a local SQLite database (using Room). When the user is offline, the app would serve the data from the cache. Implementing a robust caching and synchronization strategy is non-trivial, and many templates do this poorly.

Simulated Benchmarks

The app's performance is largely dependent on how efficiently it handles images and lists. Smooth scrolling in RecyclerView requires proper implementation of the ViewHolder pattern and efficient image loading (using a library like Glide or Picasso). If the app tries to load full-resolution images into list items, scrolling will be extremely janky. The user experience is also tied to API response times. If the backend server is slow or the database is poorly indexed, loading new screens of content will feel sluggish. A well-built app will feel snappy, with network-loaded images fading in gracefully. A poorly built one will stutter and show blank spaces while waiting for data.

The Trade-off

You get a complete, end-to-end system for a content-based app, including the client app and the backend CMS. This is a significant head start. The trade-off is that you are now responsible for two codebases (the Android app and the PHP backend) and, more importantly, you are responsible for content creation. The app is an empty shell. Its value is zero without high-quality, unique, and useful travel content. This is a massive undertaking. You are not just an app publisher; you are a travel guide publisher. The technical work of setting up the template is dwarfed by the editorial work of creating and maintaining the content.

Sky Troops Unity Casual Air Shooter Game

Sky Troops brings us into the classic "shmup" (shoot 'em up) genre. This is a top-down or side-scrolling shooter where the player controls a ship, shoots enemies, and dodges projectiles. As a Unity template, it builds on concepts we've already seen but adds a few layers of complexity. The architecture will revolve around several key systems: a player movement/shooting system, an enemy spawning system, a projectile system (for both player and enemies), and a collision detection system for handling hits. Unlike simpler hyper-casual games, a shmup often includes more sophisticated elements like enemy waves, boss battles, and power-ups. This requires a more robust level-design or wave-management system. It might be driven by a ScriptableObject in Unity that defines the sequence of enemies for a level, or it could be time-based.

Under the Hood

-

Player Control: The player's ship movement is tied to touch input (dragging the ship around the screen). A

Shootingscript, often on a timer or a coroutine, will continuously instantiate bullet prefabs from one or more "hardpoints" on the ship. -

Enemy Spawning and AI: An

EnemyManagerorWaveManageris responsible for spawning enemies. Enemies might enter the screen following predefined paths (using animation curves or a simple pathing system) or with simple AI (e.g., "move downwards and shoot periodically"). -

Object Pooling: This is critical. In a shmup, hundreds of projectiles can be on screen at once. Instantiating and destroying all of them would kill performance. A robust object pooling system for player bullets, enemy bullets, and even some common enemies is an absolute necessity for a functional template. This is the first thing an architect should check in the codebase.

-

Collision Logic: The physics engine's trigger system (

OnTriggerEnter2D) is used for everything. Player bullets hit enemies, enemy bullets hit the player, and the player can collide with enemies. Each interaction triggers a different outcome: destroy the enemy and add score, reduce player health, or trigger a game-over.

Simulated Benchmarks

A well-optimized shmup using object pooling can handle a surprising amount of on-screen action while maintaining 60 FPS. The bottleneck is typically "overdraw," where multiple transparent sprites (like explosions and projectiles) are rendered on top of each other, taxing the mobile GPU's fill rate. If the template uses complex, multi-layered particle effects for every explosion, performance will suffer on low-to-mid-range devices, especially during intense boss battles. A benchmark would involve profiling the game during a "bullet hell" scenario. A good template will stay above 50 FPS, while a poor one will dip into the 20s or 30s.

The Trade-off

You're buying a feature-rich game framework that is more complex and engaging than a typical one-tap game. The Unity project gives you a great starting point for designing levels, creating new enemies, and adding power-ups. The trade-off is increased complexity. Modifying a shmup template requires a better understanding of Unity and game architecture than a simpler game. You need to understand object pooling, wave management, and the interaction between multiple complex systems. Furthermore, while not as saturated as the "ball jumping" genre, the mobile shmup market is still very competitive, with many high-quality free-to-play titles that have years of content and polish.

Bluetooth Device Battery Level – HeadSet – Bluetooth Devices and Pair – Bluetooth Notification

This is a pure utility app template, and its name is a classic example of App Store Optimization (ASO) keyword stuffing. The app's function is to connect to Bluetooth devices (like headphones or speakers) and attempt to display their battery level. This is a notoriously difficult feature to implement universally because there is no single, standardized Bluetooth protocol for reporting battery levels. Different manufacturers use different proprietary methods. Architecturally, the app is built around Android's native Bluetooth APIs (BluetoothAdapter, BluetoothDevice, BluetoothGATT). It will perform a device scan, allow the user to pair with a device, and then attempt to connect to the device's GATT (Generic Attribute Profile) server to find a characteristic that reports battery status. The most common (but not universal) standard is the Battery Service (BAS) profile, but many devices, including Apple's AirPods, use their own non-standard methods.

Under the Hood

-

Bluetooth API: The core of the app is constant interaction with the

android.bluetoothpackage. This involves requesting user permissions (BLUETOOTH,BLUETOOTH_ADMIN,ACCESS_FINE_LOCATIONfor scanning), managing device discovery, and handling connection states. -

GATT Services: Once connected to a device, the app performs service discovery to see what profiles the device exposes. It will specifically look for the UUID of the standard Battery Service (0x180F) and its Battery Level characteristic (0x2A19).

-

Proprietary Protocols: A good version of this template might include hard-coded workarounds for popular devices. For example, it might know how to listen for specific broadcast packets from certain brands of headphones that contain battery information. This part of the code is brittle and requires constant updates.

-

UI and Services: The UI will be a

RecyclerViewlisting nearby and paired devices. A backgroundServiceis likely used to maintain a connection to a device and provide a persistent notification showing the battery level, which is the app's main value proposition.

Simulated Benchmarks

The app's performance is not measured in FPS but in reliability and battery consumption. Bluetooth scanning and maintaining a connection are battery-intensive operations. A poorly written app can significantly drain the user's phone battery. The app's main function—getting the battery level—will be unreliable. It might work perfectly for 30% of devices, intermittently for another 30%, and not at all for the remaining 40%. User reviews for such apps are often a mix of "works perfectly!" and "doesn't work at all," entirely depending on the specific Bluetooth headset they own.

The Trade-off

You get an app that targets a very clear user pain point. Many users want to see their Bluetooth device's battery level on their phone. The trade-off is that you are selling a promise that you technically cannot keep for all users. The underlying technology is fragmented and unreliable. Your business becomes a game of managing user expectations and trying to add support for new devices on a case-by-case basis. This is a high-maintenance product that will generate a constant stream of support requests and negative reviews from users whose devices are not supported. You are building on a foundation of shifting sand.

Ballz Puzzle – Unity Game

Ballz Puzzle is a template for a game in the "brick breaker" or "physics puzzle" genre, popularized by games like BBTAN and Ballz. The player aims and shoots a stream of balls to break numbered blocks on the screen. Each hit decrements the number on a block, and the block is destroyed when it reaches zero. After each shot, the blocks move down one level. The game ends if the blocks reach the bottom. This is an architecturally interesting template because it combines physics, strategy, and a satisfying core loop. Built in Unity, the project will have several key components. A PlayerController will manage the aiming line (often drawn with a LineRenderer) and the launching of the balls. The blocks are prefabs with colliders and a script to manage their "health" value. The most complex part is managing the large number of balls, which all need to have their physics simulated simultaneously.

Under the Hood

-

Ball Management: This is the core architectural challenge. Simulating physics for hundreds of balls at once is expensive. The template must use

Rigidbody2Dfor the balls and rely on Unity's highly optimized 2D physics engine (Box2D). The balls are almost certainly managed by an object pool. -

Level and Grid System: The blocks are arranged on a grid. A

LevelManagerorGridManagerclass is responsible for spawning new rows of blocks, managing their positions, and shifting them down after each turn. -

Collision and Scoring: The

OnCollisionEnter2Dmethod on the block's script is called when a ball hits it. The script decrements its health, updates its visual state (e.g., changes color or text), and destroys itself if health is zero. TheGameManageris notified to update the score. -

Game State Machine: The game has very distinct states: "Aiming," "Shooting" (while balls are in motion), and "Animating" (as blocks move down). A state machine is essential to prevent the player from aiming while balls are still moving.

Simulated Benchmarks

Performance is directly tied to the number of active balls. With 10-50 balls, the game should run smoothly. When the player has collected hundreds of balls, a single shot can introduce 200-300 physics objects into the scene. This will stress the CPU. On a mid-range device, FPS could drop from 60 to 30-40 during these intense moments. A well-optimized template will use efficient physics settings and ensure the balls are recycled quickly once they go off-screen. A poor one will lag significantly, making the game's most exciting moments the least playable.

The Trade-off

You acquire a template for a highly addictive and proven game genre with a very satisfying core loop. The potential for long-term player retention is much higher than in a simple one-tap game. The trade-off is that this is a more complex system to customize. Adding new types of blocks, special balls, or unique power-ups requires a solid understanding of the existing architecture. The balance of the game is also delicate. Changing the ball speed, block health progression, or spawn rates can easily make the game either trivially easy or impossibly hard. You are not just buying code; you are buying a pre-balanced game system that can be difficult to alter without breaking it.

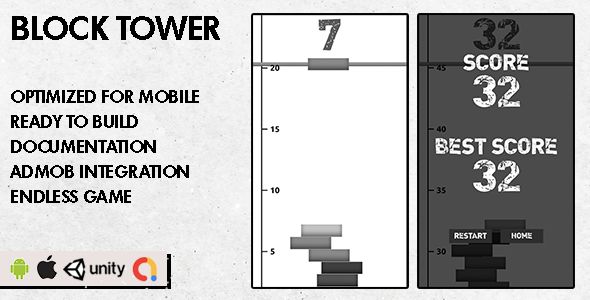

Block Tower – Unity Game

Finally, we have Block Tower, a template for a physics-based stacking game. The objective is to build the tallest tower possible by dropping blocks on top of each other. The player typically controls a block moving side-to-side at the top of the screen and taps to release it. The challenge comes from timing the drop perfectly to land the block squarely on the stack. Misaligned blocks make the tower unstable and more likely to collapse. From an architectural standpoint in Unity, this is a straightforward physics simulation. Each block is a prefab with a Rigidbody component, allowing it to be affected by gravity and to collide with other blocks. The game's core logic is in a GameManager script that controls the spawning of the next block and checks the state of the tower. A key mechanic is often that if a block is placed perfectly, no part of it is cut off. If it's placed imperfectly, the overhanging part is sliced off, making the next block smaller and the game harder.

Under the Hood

-

Block Control: The currently active block (the one the player is about to drop) is controlled by a script that moves it back and forth using

Mathf.Sinfor smooth motion or simple position updates. When the player taps, the script detaches the block from its control and enables itsRigidbodyto let physics take over. -

Stacking and Slicing Logic: When a block lands, a script checks its position relative to the block below it. Based on the offset, it can decide to procedurally generate a new, smaller block to represent the correctly placed portion and a "cutoff" piece that falls away. This is a more complex implementation that requires some mesh manipulation or clever scaling of prefabs.

-

Camera and State: As the tower gets taller, a camera follow script will smoothly pan upwards. The

GameManagerdetects a game-over state when a block is dropped and completely misses the tower, falling off-screen. -

Physics Settings: The "feel" of the game is highly dependent on the physics settings: the mass and drag of the blocks, the physics material's friction, and the global gravity settings. These values are often exposed in the Unity inspector for easy tweaking.

Simulated Benchmarks

Performance in this game depends on the number of rigidbodies in the scene. As the tower grows to 50 or 100 blocks, the physics engine has more and more interacting objects to simulate. On a mid-range device, the game should hold 60 FPS for the first 30-40 blocks, but may start to see slight performance degradation as the tower becomes very tall and complex. If the tower collapses, the sudden introduction of 50+ independently moving rigidbodies can cause a significant, albeit brief, frame rate drop. The template's quality can be judged by how well it handles a tower collapse—a good one remains stable, a poor one might crash.

The Trade-off

You're buying a simple, intuitive, and visually satisfying game concept. The physics-based nature makes every playthrough slightly different and unpredictable. The trade-off is that, like other hyper-casual templates, it's a very common genre. Differentiation is key. Furthermore, the game's core "feel" is entirely dependent on the tuning of the physics parameters. A template might provide a functional game, but it might not feel "right." The developer who buys it will need to spend considerable time tweaking physics values, block speeds, and camera movements to achieve that elusive, satisfying gameplay that encourages players to try "just one more time."

评论 0